In cosmologies across cultures, the world begins with a sound. In Hindu thought, it is this resonance of ‘aum’ which spills into the pulse of creation. Trembling deeply into the threads of life around and within us. A sound carried through the invisible lightness of breath.

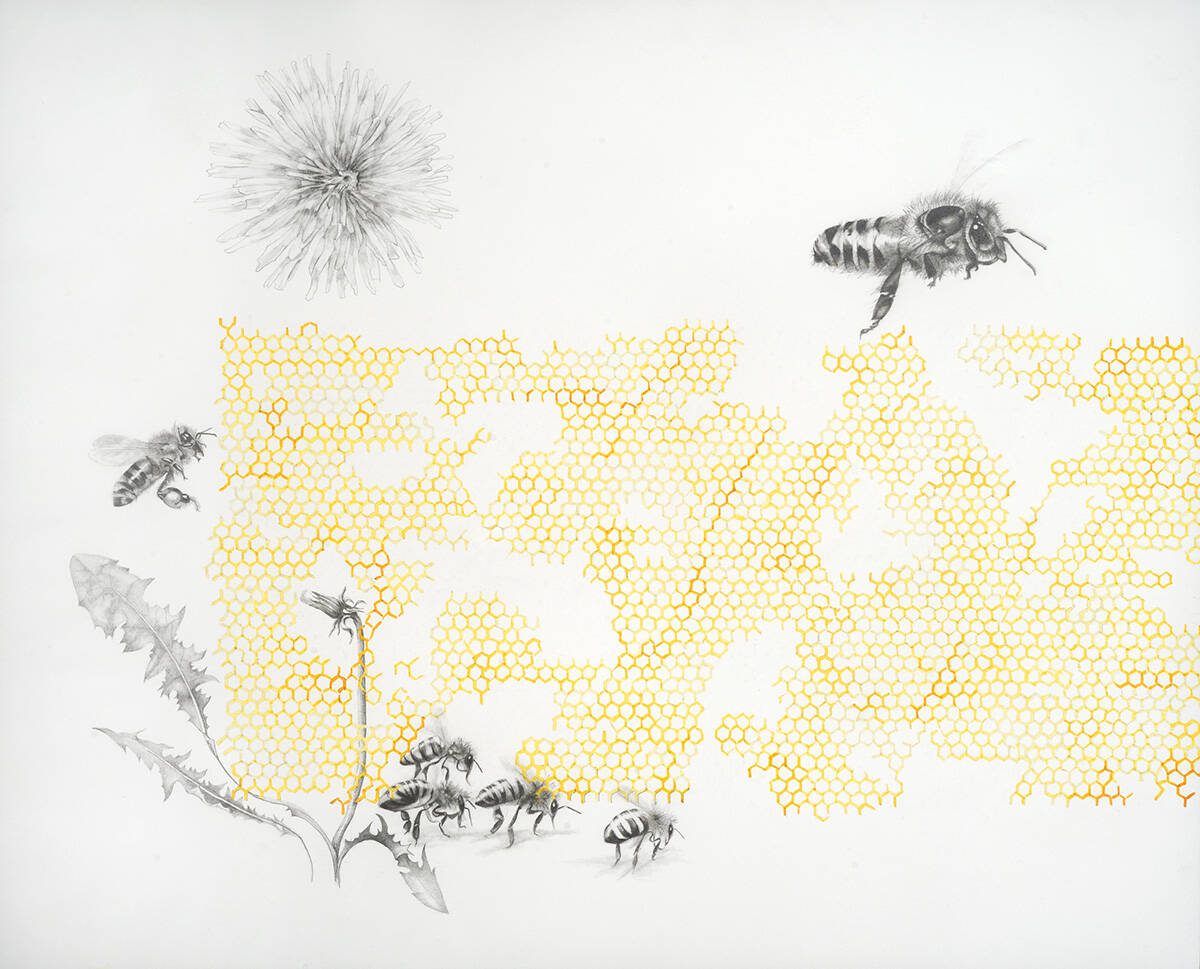

Pranayama, the exercising of breath in the practice of yoga, focuses attention towards this unseen life force which sustains us. One of these is bhramari pranayama, or bee breath. In holding thumbs over the ears, the vibrations of a humming sound are created. These are directed towards the top of the brain, the cranium, where the seventh chakra is located. This breathwork replicates the rhythmic movement of the thorax which produces the bee’s beating wings.

Overlooking Goan paddy fields, coloured by the chirpings of tropical birds and spots of all sorts of winged creatures, I practise this breath for the first time. My lips start softly vibrating, and a resonance much deeper and more sustained than default breathing emerges. This vibration clears external sight and sound with one continuous hum. Everything else, from the grazing peacocks to the busy dragonfly, fades away.

After three different tones and trials of ‘buzzing’, I open my senses to the outer world. The paddy fields are, of course, still there. The green strings sinking comfortably into their mud. They seem, though, somewhat calmer than before. The bee breath casts a net of intangible connection to the body, expanding a more subtle connection to the outside world. It is this humming breath that gives the sensation of being underwater, revealing the immediacy of both body and breath. In the aftermath of the bee breath, the sounds which sustain the universe seem more united, carrying an ease both within and beyond my body. A vibration moving as pollen does through plants.

Each pranayama has nuanced effects; the deep vibrations of the bee breath differing, for example, from chanting ‘aum’, whereby the body seems to resound into its surroundings like the base of a singing bowl. However, attention to any of these breathing practices acts as a foundational force of life which has been practised for centuries. One which lies unseen and invisible.

If it is sound – whether a hum, a vibration or a buzz – which has created this Earth, then it is sound which connects us to creation. Which brings us to a deeper attention. A microscopic force, as potent as it is small, towards that which is less visible. The way of the breath allows a way of noticing how life is not only formed, but continues. In the small movements and music in the beating of bee wings. Through pranayama, or breathwork, we are moved beyond sight and into sound. Through this practice, we need not see, but only feel.

Breathwork reverberates through noticing this subtle essence, where sound reveals the oneness in all. The practice of pranayama carries the core concept of nondualism, which was established in Advaita Vedanta, a classical school of Indian thought. According to this Vedic philosophy, the Self, Truth and Brahman (the ultimate reality) are all of the same essence. This can be glimpsed in a few seconds of attentive breathing, like replicating the beating thorax of a bee. Spinning in cycles, breath reaches into the underlining fabric of life, streaming out to touch all of existence. And so the web is strung out further, like the invisible spinning of a spider stretching further and further.

As a connector, as well as a singular point of focus, breath carries within it the fluid dynamism of conversation. The chatter between the bluebell and the bee. Or, as the Upanishads were formed, through a dialogue between teacher and student. These ancient Sanskrit texts, going back to around the 6th century BCE, encapsulate the core of Indian philosophy, and are known not only for their insight into consciousness and the nature of reality, but also for the rich oral culture of their origin, promoting the shared exchange of knowledge. In these texts, understanding truth not only follows rigorous scriptural understanding, but involves lived interconnection with the wider world. The sound of conversation flourishes through a merging, a pollinating.

The Chandogya Upanishad tells the story of Shvetaketu, who returns from the forest after 12 years of studying the Vedas, and learns from his father what cannot be solely taught from the intellect. This connection to the Earth is vividly recalled through a sense of unity. A truth which lies beyond both words and scripture, buried within an attention to the intrinsic nature of creation:

“As bees suck nectar from many a flower and make their honey one, so that no drop can say ‘I am from this flower or that’”.

It is this colourful analogy which illuminates many messages within Vedic philosophy. One such message is the illusion of separation, as revealed through the symbiotic process of pollination. Here the verse expands singularity to take the multitude of the natural world into account; its abundance of flowers condensing into the sweetness of a ‘drop’. Just as breath and sound work their way through the world, this simile reveals what is not immediately visible. Though honey is seen as honey, it is interlaced in its dependency on pollinators and the pollinated. All flowers merge into a stream of oneness.

The father continues fleshing out this metaphor, where “all creatures, though one, know not they are that One.” He draws attention to the truth that lies beyond, beneath and around our immediate eyeline. The subtle essence. The small sounds. A reality which weaves itself into an innate connection to the breath, just as the practice of pranayama carries a connection to the Self and our surroundings.

What the Upanishads call the ‘hum of the Earth’, the sound of the ‘aum’, and beginning of all creation, is bound by breath. What happens when we listen to the root of all invisible things, to what drives the propelling of bee wings?