HOLT WAS A strange fellow: he believed the human race was redeemable. We spent seven years together, digging up passage graves in Ireland, and during all that time neither his reckless optimism nor my incorrigible pessimism – though I would call it realism – ever sought the upper hand. We agreed on the basics: that the prehistoric landscape was ritualistic, a kind of sacred theatre, and that it concerned the relationship between the living and the dead. From that fundamental point – itself contentious – our beliefs diverged. This was back in the nineteen-sixties, when nuclear rather than climatic threat was uppermost in anxious minds. As I trowelled deeper into the peaty earth, into the impossible silence of that voiceless, wordless past, I was convinced that we were living at the very end of the human story. A long gangplank, I would see it as. Beneath me, beyond my toes, nothing but the depthless swirl of atomic clouds. The spirals carved on the threshold of our chambered tomb at Cloghbeg felt like a prophecy.

I was in the throes of divorce at the time, with two children to worry about. Holt was single, and peculiarly bereft of domestic ties. He saw our industrialised present as a temporary darkness before the light, when our old relationship with the landscape and its hauntings would bloom again. Our excavation was a sign, to Holt, of recovery. To me, it was a last bone tossed onto the mountainous midden of knowledge. We never quarrelled, even when the wind had ripped off the tarpaulin and our necks were soaked, our faces streaked with the soil of County Meath.

“This is happiness,” Holt would say from time to time, ensconced before a blazing fire in our rented cottage (a gloomy place with untraceable draughts) at the end of a stiff day; “so why the devil shouldn’t it last forever?”

The phrase was a puzzling, repeated motif I never properly analysed; I was too distracted – heading, as I now believe, for a breakdown. I had failed to reconcile the long-vanished past and the vivid present: in my left hand, a gloriously carved flint mace-head; in my right, a telephone receiver in which a solicitor’s voice was bundled like old string.

It was on one of those evenings, towards the end of`our time together, that Holt saved me.

WE HAD BEEN staring into the fire for a while without speaking, weary of limb, settled in a fume of fine whiskey and pipe-smoke, our skin contentedly aglow from days spent out of doors in the cold salt air where our eyes would see nothing before them but close-up earth, and close-up stone, and the intermittent relief of a sweeping, boulder-stitched beauty, when Holt said, in a voice so low I took it as a continuation of some interior thought: “What happens, then, when the dead are not satisfied?”

Surprised, I somewhat jocularly returned, in my cynic’s way: “I suspect no-one can be satisfied with being a corpse.”

“Not satisfied with their grave goods, I mean?”

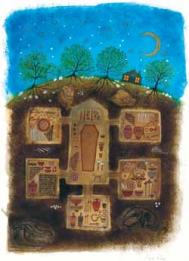

He raised his eyes towards mine; they had a fierce intentness I had not seen before. I shuffled a log into place with the irons. The carrying of goods into the next life was of such crucial importance to the prehistoric mind that it had left the archaeologist, many thousands of years later, with a welter of precious artefacts: the question had never crossed my mind.

“Well?” he insisted.

I settled back and puffed meditatively on my pipe, wondering if it wasn’t about time we – or at least he – took a holiday.

“I think”, I said, eventually, “you are working towards a conjecture that will dissolve in the acid of guesswork. Our ignorance of the Stone Age mind makes even the most solid-seeming hypothesis fatally problematic. What an historian would call unhistorical, rather than pre-historical.”

He gave a dry chuckle. “My dear Tanner, your well-wrought phrases are a smokescreen. But tell me,” – and here he put his hand on my knee – “what lies beyond the smoke?”

I was slightly alarmed, as much by his sudden physical intimacy as by the vivid picture that had flashed into my mind: what I saw beyond the smoke (there was a lot of it in the cosy air of the parlour) was neither my own face, nor Holt’s staring eyes, but something dark and impenetrable. Feathers and drumming and cries. The most piercing cries.

I shrugged, determined to keep it light. “I see a mystery,” I said. “And probably a modest type of fool.”

I was pleased with my response, but Holt laughed. A short, sharp laugh that seemed to come from someone else. A Holt I had not discovered until now.

“What I see”, he said (in a tone that scraped at my nerves), “is the kindest, most charitable soul turned into an avenger.”

His hand was now covering his brow. He is half-crazed, I thought, by the efforts we have made. Recently, an article had appeared rubbishing our plans for the restoration; bad weather had held us back at the threshold of the largest burial chamber, which risked being flooded.

I felt silence was the most appropriate response. He lifted his head, gazing into the fire.

“My grandfather was that soul,” he began, so quietly I had to lean forward to catch it. “He thought only of others. His largesse was famous throughout the county. Even during the troubles, back in the twenties, his house and grounds were exempted, despite soldiers being billeted in the west wing. As a child, I would find their rusty cartridges and imagine the blood, the cries, when there had been nothing of that sort. I and my parents occupied the east wing. The remains of a causewayed enclosure lay in the grounds. Little by little we revealed it. This was the nineteen-thirties, remember: to everyone else but my grandfather, it was an Iron Age hill-fort. But he knew it was a place of the mysteries, and was deemed an eccentric. That’s where I learnt my skills, Tanner. At my grandfather’s elbow.”

I grunted, relieved that I was not the subject any more of his morbid reflections.

“He lived to be ninety-eight,” Holt continued. “We thought he was immortal. He died on Boxing Day, 1953. My father, meanwhile, had added to the family collection of books; the result was one of the finest private libraries in Ireland, some of the books so old they had pages of vellum. My mother, a pianist of some repute, had a magnificent Bechstein. I would listen to her playing in the summer, when the windows were open, as I trowelled away next to my grandfather. His kindly eyes would shine with pleasure. In the evenings, he would sit in the library and my mother would play again in the communicating room. ‘This is happiness, my boy,’ he would say, as I read on the rug beside him; ‘so why the devil can’t it go on forever?’ He continued to sit there of an evening until his last days. That’s where they found him, you see: gasping for breath at midnight, over a poetry book. He died a few hours later, quite painlessly.”

I stirred a little in my chair, and Holt raised his hand as if to silence me.

“I loved no-one more than he,” he said. “But our mistake – my Anglo-Irish father’s mistake – was to act the Protestant. No wake, no whiskey, no songs. Just the wooden coffin, and handfuls of earth on the lid. I remember my handful of earth, Tanner. It made a sound like a tiny gunshot, because there was a flint inside. It was a leaf-shaped arrowhead, a very fine one I had found myself in the enclosure’s ditch many years before, and of which I was still very proud. Nobody noticed. But it wasn’t enough, was it?”

He paused, and raised his head – perhaps to check I was still awake. Needlessly: I had a strange presentiment, a dread.

“Two days after the burial, I woke up to the smell of smoke. The bedrooms were separated from the library and music room by a corridor. Suffice to say that when I opened the library door, all I saw was flame. Within a matter of minutes, I had woken my parents and the staff and phoned the fire brigade from the hall. We stood on the lawn and watched, unable to believe our eyes, my parents too shocked to weep. The library and the music room burned to cinders, thousands of glowing pages floating through the billowing smoke like fiery angels, the piano strings snapping like some diabolic harp. And this is what I want to ask you, Tanner: was it only because the firemen arrived just then that the rest of the house was saved, not a single inch of it touched?”

I frowned and sucked on my pipe, unable to frame an answer. A long-ago trauma had surfaced again, travelling through the layers of Holt’s professional life and arriving distorted into the present.

Eventually I murmured, watching a log fall in a blaze of sparks: “Was it perhaps the lack of a fireguard?”

Holt snorted in a derisory way. “A short-circuit, they said, behind the books. Old wiring. But, Tanner, they missed one thing. The arrowhead.”

“The arrowhead?”

“In the charred struts of the piano. Now how do you think that got there?” Then, leaning forward: “It was the same one, Tanner. I had considered becoming a surgeon. From that day on, I knew where my life lay. Beyond the smoke, you see? In the domain of the ancestors, there is also a desire for happiness. And we leave them naked and bereft. That can’t be right, can it? But only the strongest can return over the threshold and take what they need to be happy. Only the very strongest, Tanner.”

LYING AWAKE THAT night, unable to sleep, I understood Holt, suddenly, and I vowed to imitate him. He wasn’t crazed at all. He had the gift of seeing the good, still glimmering in the thickest gloom. Reaching his hand into the blackened skeleton of the piano; his fingers closing on the flint. However he believed it had got there.