THE FIRST TIME I ever set foot inside a prison, I could see nothing but pain. Not just the pain of incarceration, shame and the loss of freedom, but the pain and suffering that had travelled the lonely paths of addiction and crime, leading in turn to prison sentences.

We were there to celebrate the launch of Freeing the Spirit through Meditation and Yoga, a book recently published by the Prison Phoenix Trust. This remarkable charity brings meditation and yoga to people in prison, claiming that the cell need not only be a place of incarceration and restriction: it can be a place where the spirit can find freedom, even joy.

There are many who will vouch for this from their own experience. One is John Graham, once an addict and an alcoholic, now a therapeutic counsellor; a man who was in an approved school at thirteen and a borstal at sixteen, and from the age of twenty-six to forty-five was locked into a pattern of drug addiction and prison sentences. Ten years later, a free man, he says that the greatest thing that ever happened to him was when he was introduced to meditation, and “the stark nature of the prison suddenly became a sacred place.”

How do prisoners hear about the Prison Phoenix Trust? How do they muster the courage to find out more and learn meditation in the face of fellow inmates, some of whom might be all too ready to mock? They will probably feel as low as they have ever felt, the past a source of powerful emotions like anger or resentment, the future looming threateningly ahead, the present holding as much hope as standing on the edge of a cliff. The Prison Phoenix Trust believes, and from experience knows, that this state, apparently with nothing to recommend it, can be an opportunity, a time for change and renewal. Sandy Chubb, the Director of the Trust, knows that “A heart that is smashed to pieces can feel God.” St Romuald, the founder of the Camaldolese Order, said, “Sit in your cell as though in Paradise.” Is it too much to see a connection?

Prisoners may hear of the Prison Phoenix Trust through the prison grapevine or from the Trust’s advertisement in the prisoners’ newspaper Inside Time. This will invite them to get in touch and continues, “Together we’ll set your footsteps on a journey which – at the very least – is full of surprise…”

The Trust has a small office in Oxford, which is staffed by two full-time and five part-time workers, as well as twenty volunteers. There are also, spread across the country, some ninety yoga teachers who go to the prisons to teach weekly classes in yoga and meditation.

The Trust was the inspiration of Ann Wetherall, who had heard accounts of spiritual experience among prisoners and longed to offer inmates the richness of yoga and meditation. It has two main aspects to its work. First, it supports those who write in for help in their spiritual lives or in response to hearing about the work of the Trust. A typical letter came recently from someone who had found a copy of the newsletter in a fellow inmate’s cell: “I’m feeling really stressed and missing my family. I just can’t sleep or get any peace. Thanks for any advice you can give.”

Such a letter will be carefully answered by one of the specially trained letter-writers, mostly volunteers, who receive letters from about 2,000 people a year. The prisoner will be sent resource books, tapes and newsletters and the correspondence will continue for as long as they wish, even after they are released. Most crucially, prisoners will be given support and encouragement to practise meditation daily in their cells.

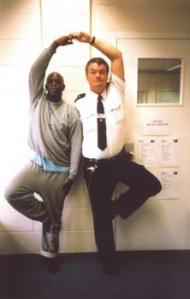

The second arm of the Trust’s work is to find and train qualified teachers to establish yoga and meditation classes in prisons. These classes are arranged in close collaboration with the prison administration; at least two prison governors attend, and of the 134 weekly classes currently being held, twenty-five are for prison officers and staff.

Prisoners who attend the classes are given practical suggestions about meditating alone, such as preparing themselves and their cell by cleaning the ashtray, looking out of the window if they have one, and placing a precious object on a clean handkerchief. Then they are taught to silence the body through moving into the postures they are shown.

Being in prison is not, I discovered, all about pain, either for inmates or for visitors; indeed one of the Trust’s teachers says her happiest moments are teaching yoga and meditation in prison. And there is ample evidence to support the effects this simple practice has on the prisoner.

There is hope, even for those who feel they cannot sink any lower. Recently, a man who was serving a life sentence began meditation. Before he started he had been fighting prison officers and smashing things up, feeling life was “a series of disasters punctuated by the odd catastrophe.” He’s not quite sure what he has found, but he says “It’s a hell of a lot more than I had in addiction. The lotus grows with its roots in mud and still produces a beautiful bloom. I finally get that!”

Freeing the Spirit through Meditation and Yoga is available from the Prison Phoenix Trust, PO Box 328, Oxford OX2 7HF, at £12.00 incl. p&p.